The Life and Loss of Empress of Ireland

This month, March 2019, marks a special and sombre anniversary known to only a relative handful of maritime enthusiasts and distant family members. On March 30 1914, 105 years ago, the Canadian Pacific Railway liner Empress of Ireland was sunk following a collision on Canada's St Lawrence River in dense fog. The ensuing chaos of the sinking, which took place in a horrifically short 14-minute span, would kill more passengers than had died on Titanic two years prior. Despite the human cost of the sinking, the story of the Empress and those aboard her has been largely consigned to the history books. Today we'll look at three special items from the Liner Designs maritime collection which each tell an individual part of the tragedy and help to paint a vivid picture of what it was like to live, and die, aboard history's forgotten lost liner.

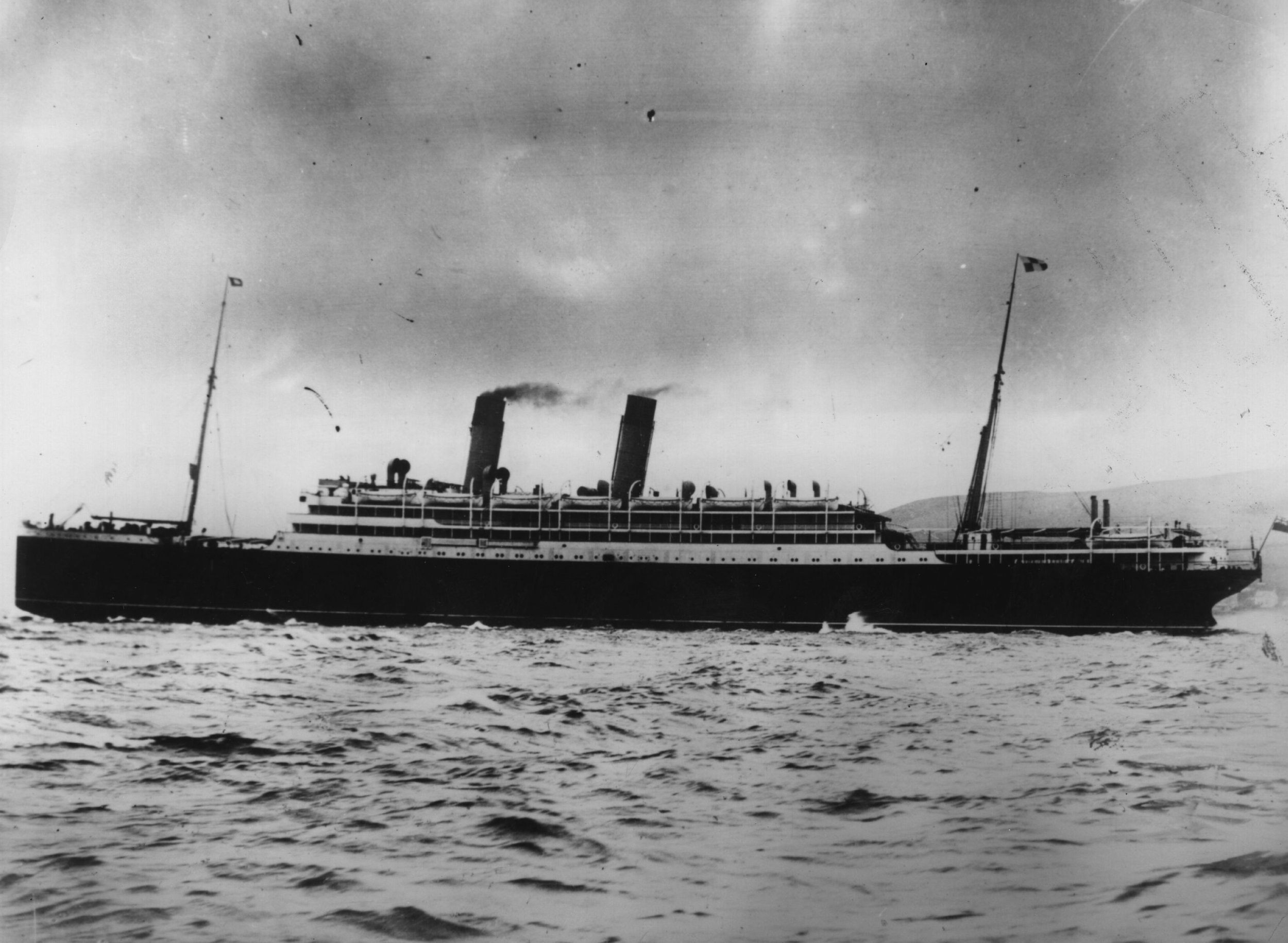

Above: Canadian Pacific’s majestic ‘Empress of Ireland’.

‘Comfort and Safety’

The Empress of Ireland existed in a world different to that of her larger and more luxurious competitors operated by Cunard and the White Star Line. While ships of those lines operated mostly on the glamorous Southampton-New York route, the Empress of Ireland and her sister Empress of Britain existed solely to carry passengers from Liverpool to Quebec from where Canadian Pacific Railway overland trains would deposit them in various corners of the country. As such, the Empresses were just one part of a vast transport web operated by the CPR; it was said that one could travel from Liverpool to Tokyo without ever once leaving a Canadian Pacific train or ship.

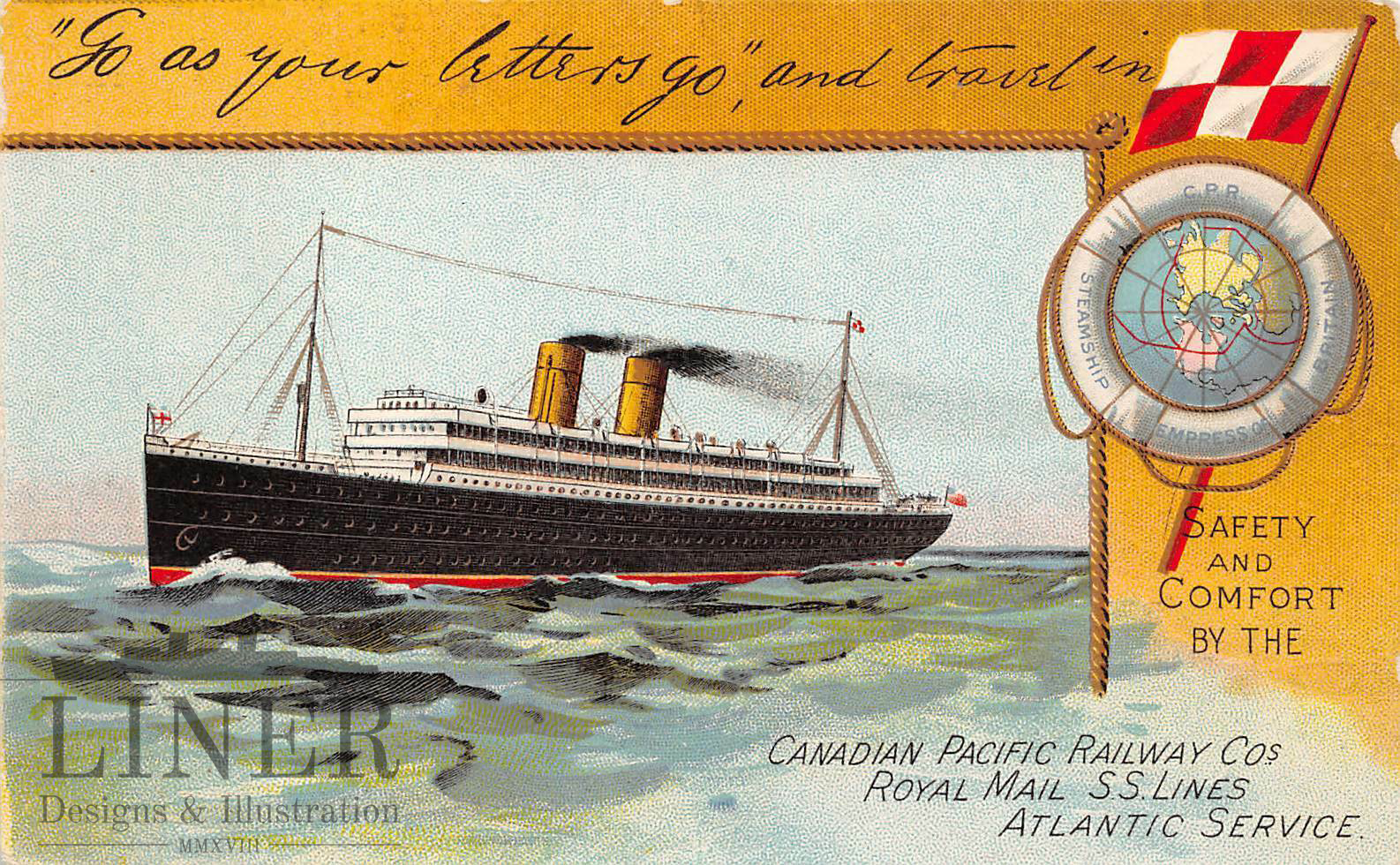

As such, it was vital that CPR's ships be up to a standard comparable with the larger ships of competitor lines operating the transatlantic trade. So it was that when both sisters were introduced in 1906, CPR could boast with pride that the two ships were among the safest and most comfortable on the transatlantic run. One effective way of spreading the news was advertising on everything from newspapers to postcards.

Postcards like this were sold aboard CPR's liners in the barbershop along with other souvenirs such as dolls. What marks this postcard out as most interesting is the emphasis on the Empresses' status as Royal Mail Steamships - the slogan "Go as your letters go" reads like a boast and indeed it was a well-earned one. Only the very finest and most reliable vessels were awarded the prestigious Royal Mail contract. One other interesting note is the tagline "Safety and Comfort". This was no idle brag either - the Empresses were certified '100A' by Lloyd's Register, marking them as two of the safest ships afloat. A subdivision of her compartments by high-reaching watertight bulkheads meant she would remain floating with any two compartments flooded, and dozens of watertight doors would contain the water's ingress. After Titanic's loss in 1912, CPR went to great lengths to fit the Empress with enough steel-hulled lifeboats for all passengers and crew.

MINTONS’ FONTENAY

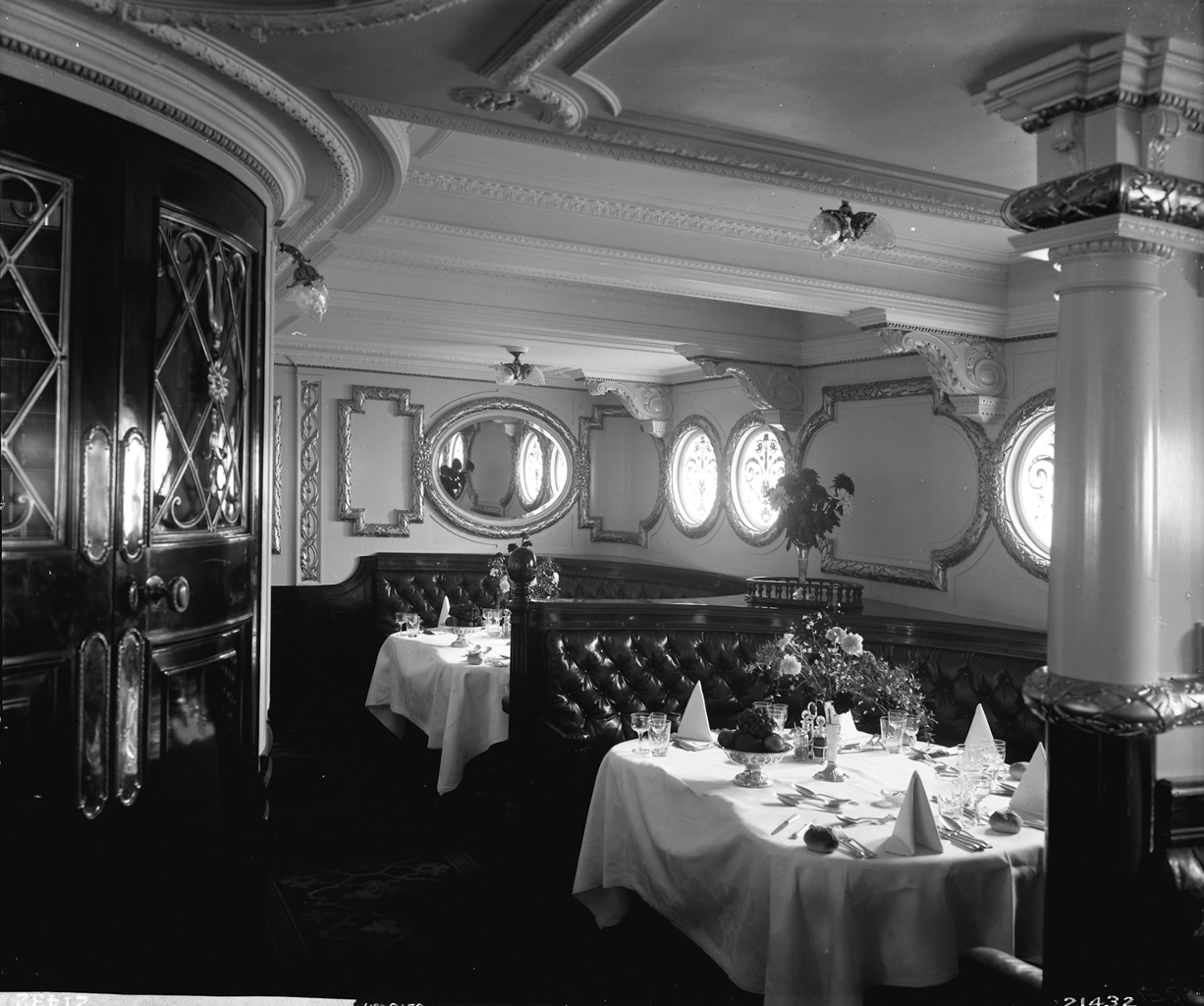

If an artefact could talk, then this fragment of China would speak volumes. It comes from Empress of Ireland's first class dining saloon, just one small piece of a large dinner plate manufactured by Mintons of Staffordshire. The Company had been commissioned by CPR to provide a fine selection of crockery for use by First Class passengers and Mintons obliged by designing a unique pattern named 'Fontenay'. This elegant, simple green floral pattern serves as an evocative metaphor for the furnishings of the Empress as a whole. While perhaps not to the same degree of sumptuousness as liners like Mauretania and Olympic, the Empresses were comfortable and inviting and marked a turning point for the conditions provided to Third Class passengers who, for so long, had contended with leaky, rat-infested and stinking quarters. Now, the Empresses provided all classes a lounge and smoking room for the week-long voyage.

Above: The sumptuous First Class Dining Saloon aboard Empress of Ireland from where our plate fragment originated.

This fragment of plate tells of the tangible effects of the Empress of Ireland's loss too. One night of March 30, Captain Henry Kendall had his ship sailing close-by the shore of the St Lawrence river which is some 50km wide. After midnight the Crow's Nest notified the Bridge that a vessel had been spotted some way off on the distance, perhaps 10km, but no immediate threat of collision was deemed possible. As such, Kendall stuck to his course intended to pass the stranger at a comfortable distance. Fate would not be kind to the Emrpess however, and at that moment a dense bank of fog rolled in across the water and obscured the ships from sight of each other. Blasting his ship's whistles, Kendall cautiously ordered his vessel's engines astern in an attempt to slow her to, or near, a dead-stop in the water to allow the strange ship to pass. What exactly caused the proceeding events has never really been concretely established as the testimonies of both captains differed substantially, but the effect was catastrophic. Peering into the fog Kendall was horrified to the lights of an unfamiliar vessel, making distant speed, appear from nowhere and closing fast.

Kendall ordered his engines full ahead in an attempt to out-pace the oncoming ship who by now was aimed like an arrow at the Empress' bridge but it was in vain; the anonymous cargo vessel plunged its heavy bows into the Empress like a knife into hot butter, crushing dozens as they slept soundly in the bunks and opening up a hole so vast that 600,000 liters of water began to enter the liner with every passing second.

Immediately, the Empress listed sharply to starboard and Kendall realised the full extant of what was about to happen. The cargo ship, now identifiable as the 'Storstad', a collier, had hit the Empress dead amidships and flooded her two boiler rooms; the crew who remained behind to try to keep her lights burning drowned almost to a man. So too did her passengers suffer; the pronounced list meant those on the starboard side could not walk up slanting passageways or halls to reach stairs leading up to the lifeboats. Lost in a maze of unfamiliar corridors, they died by their hundreds within minutes of the collision. Finally, as her steam escaped and her boilers cooled, the great ship lost all steam and her power died; the Empress was shrouded in permanent blackness.

Above: An exceptional painting by maritime artist Yves Berube shows the Empress moments after colliding with the Storstad. Already she is listing heavily to starboard. Yves’ gallery can be found here; http://www.marineartgallery.com

Some boats were launched but not nearly enough; the unbearable list to starboard saw to that. As Kendall clung to the bridge's rail and shouted commands he was lifted higher and higher as the Liner rolled. Equipment, dislodged from the rolling decks, smashed through crowds of people and plunged into the icy black water below. Finally, with a heavy groan, the Empress of Ireland rolled entirely onto her starboard side, flinging Kendall from his post like a rag doll.

In the dining saloon, freshly set for breakfast the next morning, plates, fruit bowls, chairs, tables and flower vases smashed up against the vessel's hull before being swallowed by murky river water. This shattered fragment of plate bears witness to the Empress violent final moments and ultimate demise; after only 14 minutes she was gone.

Above: An intact plate from the Empress from another private collection.

UNDER THE MANAGEMENT

OF MR LAURENCE IRVING

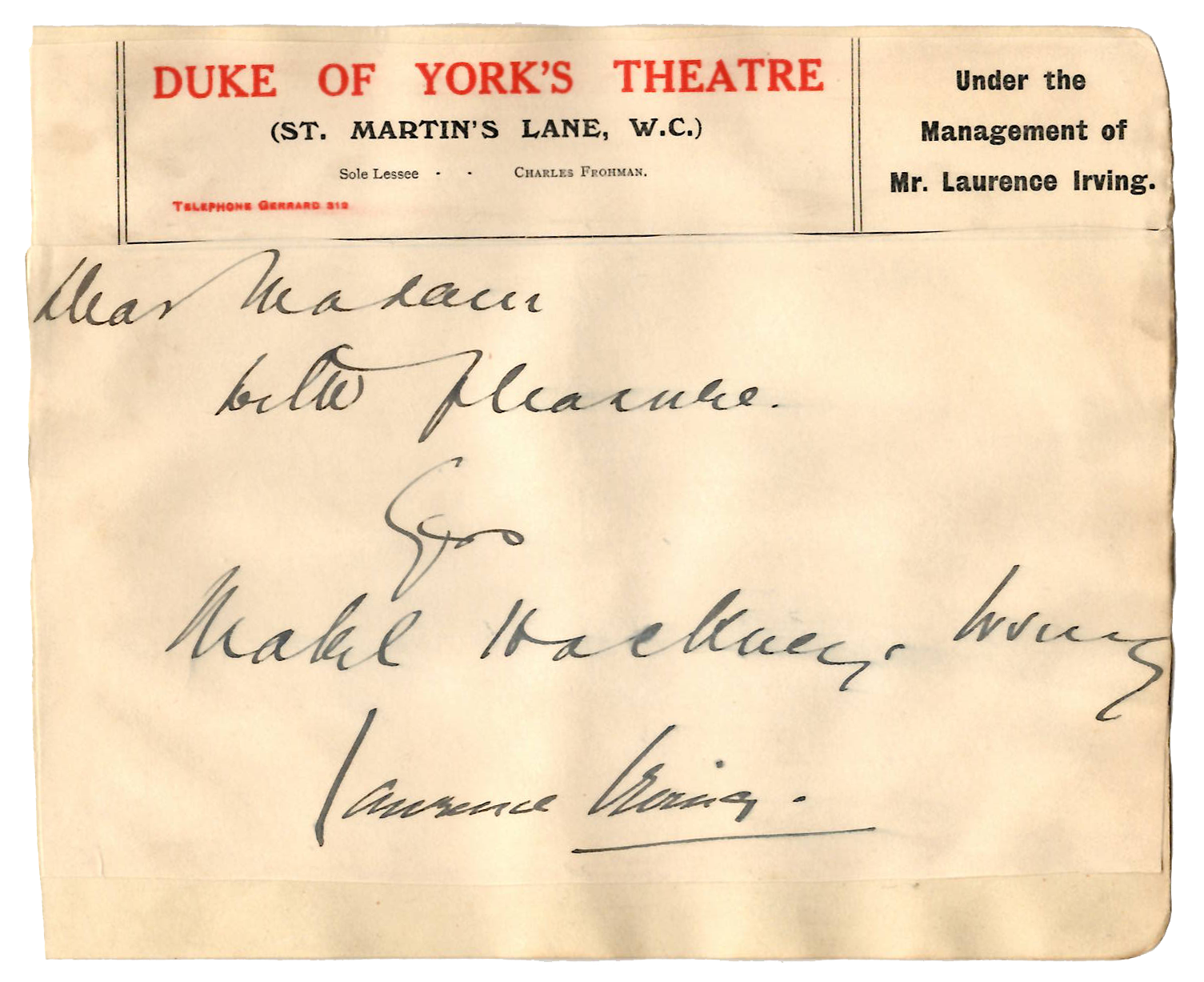

If our plate fragment can speak to us of the Empress' dying moments, then a seemingly benign sheet from a guestbook highlights one of the tragic human stories from the night and sheds light on the lives of the Empress of Ireland's two most famous passengers.

In 1906 the renowned English actor Sir Henry Irving passed away after a 50 year-long career which had seen him grace the stages of some of the world's finest theaters. Into the void left by his passing stepped his 35-year old son Laurence who had already gained some reputation as a novelist and dramatist. For the next few years Laurence's name grew as he appeared in tow highly successful plays of his own writing; 'Typhoon' and 'The Unwritten Law'. In these two plays he starred alongside his wife, Mabel Hackney, who too was highly regarded as one of England's finest actors. The couple seemed unstoppable, and performed successful tours of Australia and North America. In 1914 they had just finished a tour of Canada and were booked to return to England aboard White Star Line's Laurentic along with their troupe.

Above: A publicity shot from one the Irvings’ productions. One survivor last saw them clinging to one another as the ship sank around them.

Laurence, ever the hard-worker, convinced his wife that they should leave sooner so as to begin working on the couple's next project; a play based on the life of Napoleon Bonaparte. As such they, along with Mabel's maid, booked with Canadian Pacific and were allotted first class tickets aboard Empress of Ireland - due to sail just one day sooner than Laurentic.

That decision would prove to be a tragic one, but on that night of sailing disaster must have been the last thing on the couple's mind. After a quiet dinner, they turned in early as did the majority of passengers - it was typical to get a good night's rest on the first evening of the trip and so the Empress' elegant public rooms lay empty and mostly silent.

It is not entirely clear how the Irvings met their fates. One passenger, who had dined with the couple only hours earlier, saw the pair struggling up a slanting corridor when Laurence lost his footing and slammed bodily into a bulkhead. Bleeding from the head, he attempted to calm Mabel and forge onward to the boat deck. They would never make it off the ship; one passenger saw Irving survive aboard a lifeboat before, in a state of distress on seeing his wife was not among the occupants, he dove back into the water to search for her. Another account stated the pair were embracing on the vessel's overturned hull when they were swallowed by the River. Their bodies were never found.

Above: This period illustration shows passengers desperately clinging to the Empress’ overturned hull. Within minutes she would be totally submerged, and most of her passengers frozen or drowned.

This browned piece of paper dates to about 1911, when Irving managed the Duke of York's theater in London - perhaps at the time when the 'Unwritten Law' was being performed. Perhaps asked by a fan, Laurence and Mabel both signed the parchment in a gesture that has come to symbolise their eternal bond. They were inseparable in life, in work, in love and finally in death and their twin signatures today exist as a reminder of, not just their loss, but of all those who perished when the Empress of Ireland disappeared.

Above: One of a number of memorials dedicated to victims of the Empress’ loss.

The Empress of Ireland's human toll is almost unbearable to consider; 1,012 passengers and crew were killed, including 139 children. For days after, countless coffins streamed from recovery vessels - a heartbreaking number of these were child-sized. Ultimately, the speed with which the Empress sank and the looming threat of war meant that the ship's foundering was but a mere blip on the world stage. Where as Titanic had commanded the public's interest and not let go its grasp, the Empress of Ireland's sinking was quickly forgotten. Perhaps the notion that a safe, modern vessel fully-equipped with more than enough lifeboats for all aboard could sink in 14 minutes with the majority of its human complement was just too much to consider.